A Lunch with Sally Quinn: Still Turning Heads

Matthew Cooper joins the legendary journalist and novelist at Martin’s Tavern to talk old Washington, her new novel, and the lessons of a life fully lived.

By Matthew Cooper

We should all look so good.

Sally Quinn, at 84, still turns heads, especially when the journalist and novelist strolls into a Georgetown landmark, Martin’s Tavern, a modest walk from her home. Like Quinn, the tavern is a Washington institution. Locally and family owned since it opened its doors in 1933, it still has the “Proposal Booth” where a young Senator John F. Kennedy asked Jacqueline Lee Bouvier to marry him, and the table where Senate Majority Leader Lyndon Johnson and House Speaker Sam Rayburn cut Texas-sized deals and sipped Old Fashioneds. With its dark-stained wood paneling, Tiffany-style lamps, and elevated comfort-food menu—steaks, chops, and once-popular classics like Welsh Rarebit and the Hot Brown—Martin’s Tavern is perfect, even more so when we settle into the booth named for Sally, her late husband Ben Bradlee, the longtime Washington Post editor, and their son, Quinn.

The place is loud and boisterous during this July lunch service, but we were here for Silent Retreat, her new novel. It’s a theological romance (not an oxymoron) set at a Virginia monastery. Enter Sybilla Sumner, a 39-year-old lithe New Yorker writer in a loveless marriage to an egomaniacal TV host (think a mean, hyper Charlie Rose but with the handsome good looks of the late journalist Jim Hoge ). Having lashed out after recently learning he’s infertile, it’s no wonder Sybilla seeks comfort and direction BY heading to a spiritual retreat.

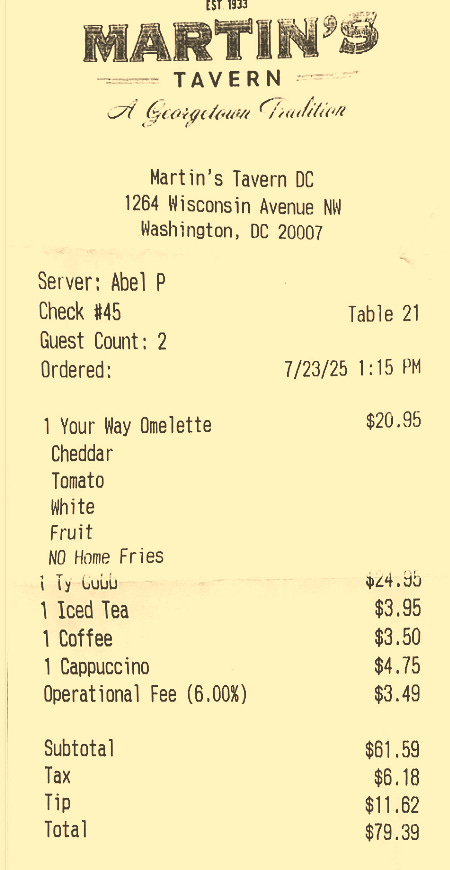

Trouble starts when she spies the Archbishop of Dublin, Father James Fitzmaurice-Kelly, “Fitz” to everyone—a motorcycle riding, Bono-esque, guitar playing, 50-something hunk of burning priestly love who’s going through his own existential crisis as the Vatican gets ready to give him a dressing down, or worse, over his latest liberal tome, Why Celibacy? Of all the monastic retreats in the world, why, oh why, did he walk into this one? Fitz and Sybilla recognize each other; each has been a bit obsessed with the other's writing, but neither can talk about it or anything else at the silent retreat. “I always thought there was a connection between sexuality and religion,” Quinn said, over her omelet, with fruit, no potatoes. “To me, there's nothing dirty about sex, certainly not sex between people who are in love. I mean, I think that's sacred.”

Quinn’s not big on priestly celibacy: “[It] doesn't make any sense…it had nothing to do with Jesus or the Bible. It was about not wanting people to marry so they could leave their lands to the church. It's all about ‘money talks and bullshit walks,’ and so it has nothing to do with anything religious.”

She adds that the idea for a love affair that begins (and ends? You’ll have to read it.) on a silent retreat came to her when she visited Our Lady of the Holy Cross Abbey in Berryville, Virginia, for just such a respite some 15 years ago. It’s about an hour west of here. No tryst for her. She’d gone there as part of a PathNorth retreat, an organization of CEOs who try to do well by doing good. Steve Case of AOL fame is one of the founders.

Quinn, who had begun her own spiritual journey and was writing the On Faith column for The Washington Post, was happily married to Bradlee, who joked that she couldn’t last three days without talking. She found the pastoral retreat with its enforced silences, bucolic setting, multiple prayer sessions (even one at 3:00 a.m.), and pastoral counseling (where you could speak) to be profoundly spiritual (no surprise) but also soothing (again, not shocking), and more erotic. “I found it very romantic and sensual,” Quinn adds. For years, she kicked around the idea of writing a novel based on a silent retreat. When it finally came to her a couple of years ago, it spilled out. She wrote it in six months.

At its heart, the novel is not only theologically knowing (references to Buddhism, the late monk and author Thomas Merton, and the Talmud) but also wise in dealing with the question of vows and obligation. Sybilla doesn’t want to violate her marital oath. While the handsome, worldly Fitz has publicly questioned the church’s stand on celibacy (as well as its positions on homosexuality and women in the priesthood), the curly haired demigod takes his vow of celibacy seriously, not only because he took an oath to the church and God but also, we discover, because of a tragic love story in his past. Can our two tortured types figure this out? And, hey, how does a novelist handle dialogue where the protagonists don’t speak?

As I picked at my Ty Cobb salad, (a baseball coach founded Martin’s Tavern) I listened to how Quinn constructed a story with two interior monologues, what’s going on in Sybilla and Fitz’s heads, and their separate counseling sessions with Father Joseph, the learned and refreshingly non-judgy octogenarian cleric they meet with regularly to discuss their inner torment. (Quinn’s counselor at the Berryville retreat, who sadly died during the pandemic, was a model for Silent Retreat.) I read the book and listened to the audio version with male and female narrators and found it a great summer read, but more than that, actually quite moving as each of these seemingly successful, beautiful souls wrestles with themselves. Did I smile and roll my eyes at the many pairs of lacy underwear Sybilla brought to the monastery? Yes, I did, happily so.

Like her protagonists, Quinn is one of the beautiful people. And like them, she has had to wrestle with life’s hardships. Her late husband Ben, who died in 2014 at 93, was legendary, a word too often used, but it’s entirely accurate. As was said of James Bond, women wanted him, and men wanted to be him. He was fantastically handsome, smart, and fun as hell. Sally took care of him as he had dementia before he passed. Her son, Quinn, now entering middle age, who is taking a stab at the Mezcal business with his wife, has worked hard to overcome learning disabilities. And she’s had career ups and downs; Quinn went through a brief stint as a CBS Morning News anchor in 1973 before returning to the Post, but got a fabulous book out of it.

Another great book of hers is Finding Magic, a touching account of her faith and journey from childhood Presbyterian to atheist to SBNR, spiritual but not religious. Her favorite bumper sticker is “I Don’t Know, And You Don’t Either.” She’d grown up Presbyterian in a military family; her father, Lieutenant General William Wilson "Buffalo Bill" Quinn, helped liberate Dachau, but the household staff in the South knew voodoo. Quinn’s mother suffered strokes, and so did she about a year ago, and was incapacitated for a brief period. With the help of Robert Waldinger, the Harvard psychiatrist, and meditation and medical care, she returned from it. “I feel like I’m nicer to other people and more caring,” she says. Those who’ve suffered her lash may wish to trust and verify.

Like many people, Quinn is distraught by division in the age of Donald Trump. I ask her if Washington feels more riven than the rest of the country or somehow spared because of its once prevalent we’re friends after five " ethos. After all, she was known as a great writer and Washington’s preeminent hostess, and it didn’t matter if the president was Democratic or Republican. Unless the fever breaks, I wonder if there could be another Sally Quinn or Perle Mesta (See Meryl Gordon’s biography of the pre-Sally hostess with the mostess). Quinn’s not optimistic about a return to the salad days. She notes how siloed Washington parties have become and notes a top Trump ally saying to her at one Trump-heavy event, "I wish you would stop writing all these stories about how boring and dull Washington is and how everybody's depressed and despairing and sad and having a terrible time.” The woman who sports the Mar-a-Lago look said, “We're having a great time. We are really happy. And your problem is that you're going to the wrong parties.”

“It may be the wrong parties, but not the wrong people,” Quinn replied. Thus, she’s not trying to get Trump folks to her house. “What are we going to talk about? Ukraine? We're going to talk about immigrants? Are we going to talk about the CDC? Talk about defunding cancer research or NIH.”

I ask her what her father, one of Dwight Eisenhower’s generals, would have made of Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth, or Mike Flynn, the National Security Adviser who left days into Trump’s first term and was later pardoned by him. “He would have been absolutely horrified,” Quinn tells me. “Well, the West Point motto is ‘duty, honor, country.’ I don't see where anything they do fits into that,” her voice trails off. “Pam Bondi…Tusli Gabbard.’’

If she offers a grim vision of Washington's social life, she is not so dispirited by The Washington Post, which has been her home for 50-plus years. While she cheered Amazon founder Jeff Bezos’s purchase of the paper from her longtime friends, the Graham family, she’s sad to see it going through choppy financial waters and watch many of its writers take a buyout. “That was a real period of grief,” she says

But she’s also cheered.“I think the paper is really good and Matt Murray is a really solid decent guy with good news judgment. I think he’s doing a good job,” she says of the paper’s executive editor, who had previously steered The Wall Street Journal. ”The op-ed page,” she pauses, “that remains to be seen.”

I note that some of Ben Bradlee’s successors lacked Ben’s twinkle, his sense of fun. She lights up: “Ben used to walk around the newsroom, sit on people’s desks, and ask, ‘Are you having fun today?’ We had so much fun. You come in every day, not knowing what will happen.”

Fun is very much on her mind, which is not always true of octogenarians, widows, or persons into Trappist trappings. “I do have people over a lot, but the number one reason is to have fun, and for there to be a reason,” she says. She’s in a group at the DC Improv, the comedy club. Not long ago, she had about 20 classmates over to her Georgetown home, once owned by Abraham Lincoln’s son, Robert. They were greeted with martinis and did performance exercises, including roaring like a lion. They stayed until midnight. “And then the next day, I kept getting all these emails saying, ‘Do you realize nobody mentioned Trump or The Washington Post?’”

It’s fitting that Quinn is in the middle of writing her Washington memoir. She notes that Watergate, which seemed so horrifying at the time, still pales compared to the current moment, even keeping Richard Nixon’s criminality and paranoia in mind.. “The Trump years are beyond anything you could have imagined.” She adds, “I keep trying to think of fun things to do to get everyone out of their heads.” As part of clearing her head, she joins a weekly two-hour meditation group.

I walk back to Quinn’s home with her before parting. She’s off to Greece in a few days to do research for her next novel and relax. Ben’s brother had a home on Spetses, a Greek isle that plays an important part in Silent Retreat, and she’ll be there, not for a monastic holiday but one far from the madding crowd.