José Andrés' Best Advice is Not About Cooking

To be Happy for the Rest of Your Life, Treat Every Meal as Your Last

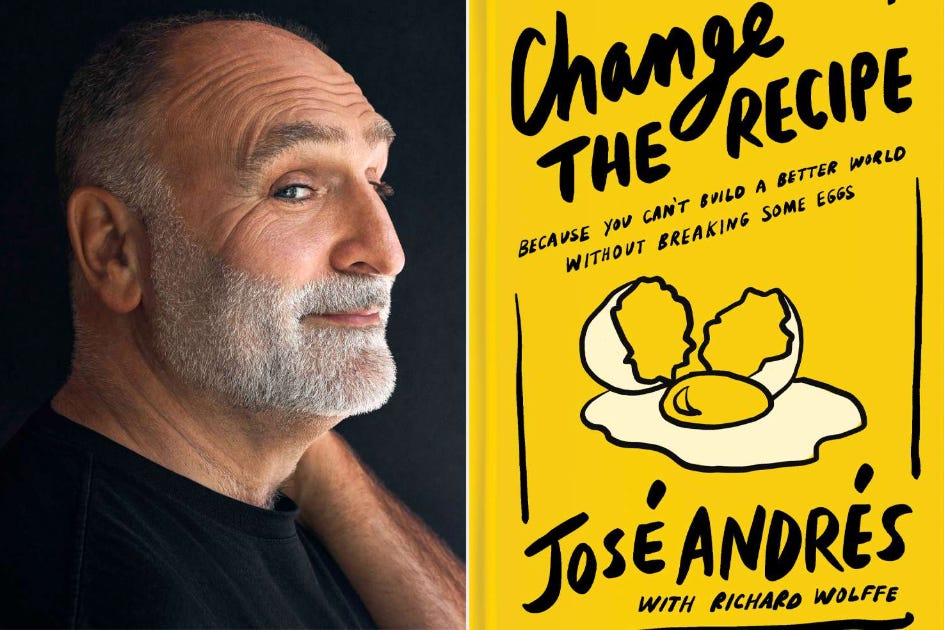

José Andrés just published “Change the Recipe,” his 17th book. The subtitle suggests a reason: “Because You Can’t Build a Better World Without Breaking Some Eggs.” It became an instant New York Times bestseller, and, incidentally, a guide that offers up food as a solution to many of the problems plaguing the world: climate, immigration, national security, and dignity. He went to the Clinton Global Initiative annual meeting in New York in late September with a plea to those in charge: “The world doesn’t run on oil. It runs on rice.”

I’m Irish. I’d say potatoes, but that’s a quibble. In case you’ve been on a low-carb diet, José Andrés is the chef who left the classroom at 15 to attend a renowned cooking school in Barcelona, and then apprenticed at a celebrated restaurant in Catalonia called El Bulli. A few years later, he boarded a ship to America with little more than a paellalero and a smile. It wasn’t long after working in several restaurants in Washington, D.C., that he opened Jaleo in 1993, a tapas bar that introduced small-plate dining. It rolls merrily along to this day with offshoots at Disney World in Florida and in the Cosmopolitan Hotel in Las Vegas.

Andrés was soon creating something completely different. After he and his family traveled the Mediterranean, he returned with an irresistible mashup of Aegean, Turkish, and Lebanese dishes. Recently, by the authority vested in me to write this piece, I went to see how Zaytinya was doing. Back when Andrés chose it for his whitewashed Greek taverna with sun streaming down through soaring windows, the neighborhood was run-down with vacant buildings and boarded-up storefronts, the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery a dead spot closed for renovation.

But the rent was right. Its neighbors now include the Capital One Arena, along with Tatte, the hot casual food chain, and swank Chanel and Hermes boutiques. Zaytinia is almost near capacity from lunch through dinner, even with the government closed down. It also has a Michelin Bib Gourmand award recognizing that it is priced reasonably enough for families to celebrate birthdays and chic enough for the expense account crowd to take a meeting. In the kitchen are line cooks who have been rolling phyllo dough for decades (nothing frozen allowed) and a front of house where it’s not just the second bowl of tzatziki (hold the pita, bring a spoon) that makes it work, or the addictive Crispy Brussels Afelia, but the “always glad you came” ambience of Cheers. You may arrive alone, but you won’t feel that way for long

In between Jaleo and Zaytinya (there are six others from Palo Alto and LA to South Beach), Andrés created some three dozen additional restaurants. His newest foray is easing the misery that is now air travel with a lounge at Reagan National, and another opening any day in the renovated Terminal B at La Guardia, a massive 10,000 square foot bistro with a view of Manhattan from the skybridge. Henceforth, the word “Delayed” popping up next to your flight will no longer induce dread so much as an eager “I’ll have another.'“

It’s more efficient to talk about what Andrés doesn’t do: he doesn’t do discouragement. In “Change the Recipe,” he fires up a metaphor to make a point about The Three Stages of Brunch. It starts with eggs meant to be fixed fancy. “You’re cooking a Spanish omelette full steam ahead. You show off and flip it, it falls apart. Stage two: Now you have a deconstructed egg and tomato mess on your hands. What do you do?”

A mess like that? I’d run next door for eggs, or to the store for something frozen, but not our hero. “People freeze and governments freeze, because we are trained to follow the plan, to be perfect. ” In crises, André sees those in charge sitting around arguing over how to amend the plan rather than how to save a country. Still, I understand the impulse. At Good Shepherd School, if I hit a wrong note during a rehearsal, my irresistible urge was to start over, going back to the beginning in a quest for perfection, until Mother Marita Joseph was close to breaking the Sixth Commandment (Thou shalt not kill) or demoting me to the lowly bassoons. It’s why I miss deadlines.

His book is not for those expecting the latest recipes, or who harbor the illusion that one day, because they like to cook, they too could open a restaurant. It’s about life, its own self, how to give it your best and give your best to others not so fortunate, and not to be a food snob in a toque who oozes ego. Think of “The Bear” streaming on Hulu or Gordon Ramsey in real life, or those annoying gourmands who spend $2,000 for a pound of hard-to-dig-up fungus to show off their refined taste for truffles.

I’ve watched Andrés over the years and joined an interview for his latest book, concluding that either he is normal, or he fakes it better than (fill in your least favorite egomaniac here). His next step, after Jaleo was up and running, was to figure out how to reduce the amount of food restaurants were wasting. To that end, he joined the board of D.C. Central Kitchen, a local charity that feeds the unhoused. It also trains men and women seeking jobs in the food industry, including his own restaurants Andrés had a mind meld with DCK’s founder Robert Egger who remembers telling Andres repeatedly how crazy whatever his latest idea was. But then, Egger noticed, “he always went and got it done.”

It’s a stretch to go from coping with a sloppy mash up of eggs in the morning to saving starving people. In that situation, if you make a plan, you’ll find a natural disaster has something else in mind. But Andrés believes that “leaving your comfort zone brings out your authentic self.” When Haiti suffered a 6.4 magnitude earthquake in 2010, he set off for the island nation, certain only that multitudes of hungry people had lost everything and he knew how to cook.

His experience scrambling to make meals at camps across Haiti –where about half a million plates of mashed beans next to fluffy rice as Haitians like it–led to the founding of the World Central Kitchen so there would be some infrastructure in place for the next catastrophe, knowing there would always be another.

The next time came during a 2017 family vacation in the Caymans with his two best friends: Anthony Bourdain, former chef at Brasserie Les Halles in New York and TV star, and Eric Ripert, the top toque at Manhattan’s Le Bernardin, who also owns a hotel and the restaurant Blue on the Caribbean island. Andrés reacted immediately to TV news reports of Hurricane Maria’s devastation in Puerto Rico. With little more than a fishing vest, one pocket stuffed with cash, the other cigars, and a habit of shouting “Boom” when things are going well and something saltier when they’re not, Andrés took off to cook for the survivors.

There would be the equivalent of omelettes falling apart, of having too few hours in the day, of switching from his way of making things for how the locals do, subbing Puerto Rican sancocho stew for the rice and beans of Haiti, to give those left with nothing, the hope that one day they would have dinner at home again.

To a man with a hammer, everything is a nail. To Andrés, a man with a whisk, every person is a mouth to be fed, whether it is a Dad wanting to celebrate a child’s graduation without a payday loan, or an entire country left homeless with nothing to eat but wrapped crackers. This time, Andrés mobilized the nascent World Central Kitchen network of local chefs and volunteers, generators, ovens and food in 18 kitchens. “I’ve learned that sometimes big problems have small solutions,” he said. “I fill a plate, then two, then four.” Before long, he’d fed a village with approximately four million meals, 100,000 meals per day at its peak, using the Coliseo de Puerto Rio arena as a central kitchen that deployed trucks of food across the island.

While Andrés was setting up dining halls built of scraps throughout the island, Donald Trump landed long enough to make a cameo appearance at a church and toss “beautiful” paper towels to a crowd as if he were shooting baskets. The president later defended his let-them-eat-cake moment by describing how joyful the natives were “screaming and loving everything” as they scrambled for the quicker picker-uppers. “I was having fun, they were having fun,” Trump insisted.

For his efforts, and without any campaigning for one, Andrés was nominated twice for a Nobel Peace Prize, in 2019 and again in 2024. Donald Trump waited in vain for notice of his paper-towel heroism from the Nobel committee. Today, however, his more mature efforts in Gaza may well be recognized in time for next year’s balloting, if the hostage release is actually followed by 12 months of peace.

As the years went on, Andrés continued his double life–part chef, part Mother Teresa. By day, he built restaurants that introduced America to Iberico ham and fusion cuisines, while also jumping on planes to places destroyed by Mother Nature, by war, by COVID where his efforts landed him on the cover of Time magazine. By night, he’d tended to the problems in arenas both foreign and domestic, and tried to snatch a few hours of sleep.

Something had to go. In 2024, the humanitarian overtook the corporate. Andrés made the difficult choice to hire a CEO to oversee the restaurants. To make sure that change left him with no spare time, he devoted himself to a new organization called Longer Tables, named for the notion that if one has good fortune, it is better to build longer tables to fit more people than higher fences to separate them. Under that umbrella, he is working to provide prosthetic limbs for Ukrainians maimed by shells and mines buried across the country, and to acquire the delicate equipment for facial reconstruction.

Andrés isn’t icky sentimental, but he believes in the power of a meal as the first glimmer to the victims of a calamity that they will live to see another day and that each one will be better than the last. Food, he writes, says “Someone far away cares about you; that you are not on your own. It’s a beacon of hope. It allows those in despair to have a little bit more patience, for one more day. That is what a plate of food is.”

A bit dramatic for some, especially journalists, who exist to expose the sinners among us, not the saints who are notoriously hard to write about given their excessive virtue that shows the rest of us up. I tried in the course of this piece, even starting over, to answer the enduring question of what makes one person build his life gradually, and then more, and then completely around the needs of others, while many, like me, construct a life around themselves. I expected to find a human weakness if I looked hard enough. As close as I came was Andrés’ odd fondness for Chick-fil-A. He’s been spotted more than once in the drive-through lane in northeast D.C., a block from the Costco that many cooks frequent. It’s not exactly a flaw, but he is a chef, after all, and he doesn’t go a few more blocks to Popeye’s for a superior Spicy Chicken Sandwich with a side of wings?

In his spare time, Andrés still produces podcasts and newsletters and promotes his latest best-seller, which shows how a person can triumph in one field and move on to a less glamorous but more gratifying one. He also picked up a Daytime Emmy for “José Andrés and Family in Spain,” a TV special made with Tichi, his wife of 30 years (whom he calls “the most amazing giver a person could have next to him”), and their three daughters. The family travelled on their respective stomachs to discover dishes worthy of bringing home. Over his long career, Andres has also won a National Humanities Medal, several James Beard awards, two Michelin stars for his minibars, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. At this very moment, his 18th book may well be gestating inside his laptop.

Andrés is no stranger to grief, surrounded but not engulfed by it whenever he touches down in one of the hundred disaster sites he’s landed at. But in 2018, grief became intensely personal after the death of his close friend, Anthony Bourdain of the trio that also includes Eric Ripert, chef and part owner of three-star Le Bernardin. Bourdain had come to shoot an episode of “Parts Unknown” in Asturias, Spain, where Andrés grew up. The two went up a high mountain to a pristine lake, the closest, Andrés said, “you can come to the stars, or to God, if you are a believer.” After the cameras were turned off, the pair lingered at the table, eating what was left of the ripe blue cheese, two best friends, in no hurry to end the day, watching the sun go down.

A week later, Andrés got a call from Ripert, who had been filming an episode himself with their mutual friend when Bourdain didn’t show up for dinner. Ripert went up to his room but by then, Bourdain had given up on life and hung himself. Since then, Ripert and Andrés have pondered how they could have missed Bourdain’s despair.

There is no answer to what-might-have-been. To honor Bourdain, rather than remember their friend on June 8, the day he died, they celebrate him on June 25, the birthday of the man they call the “troubadour and poet and lover of life.” With great joy, Andrés and Ripert raise a pitcher to Bourdain every year on Instagram to wherever he is “on his journey.”

Andrés’ book encourages readers to “change the recipe,” advice that is well worth taking to heart, although I choose to flat-out ignore it. Instead, what rings in my ears when I turn on the oven is his counsel never to take for granted that you will wake in the morning to another breakfast, to upend with misplaced bravado. Recalling his last encounter with Bourdain in Asturias and what might have been, Andrés has this advice: Since none of us knows which meal will be our last with someone we treasure, the wise thing to do is to “treat every meal with someone you love, as if it could be your last .”