Dear Friends of The American Table,

As the year comes to a close, I want to take a moment to thank you for your incredible support and enthusiasm for The American Table. Your engagement with our stories about food, culture, and politics has been truly inspiring and fuels our passion to keep bringing these conversations to life.

This holiday season, I hope your tables are filled with joy, laughter, and meaningful connections. May the dishes you share remind us all of the power of food to bring people together, no matter where we come from or what we believe.

From all of us at The American Table, we wish you a wonderful holiday season and a happy, healthy New Year. We’re excited to bring you even more stories and insights in 2026.

With gratitude!

Need a last minute gift idea? Gift your friends and family a subscription to The American Table! Click the link below to give away a subscription today!

Happy Hanukkah! Dad's Chopped Liver

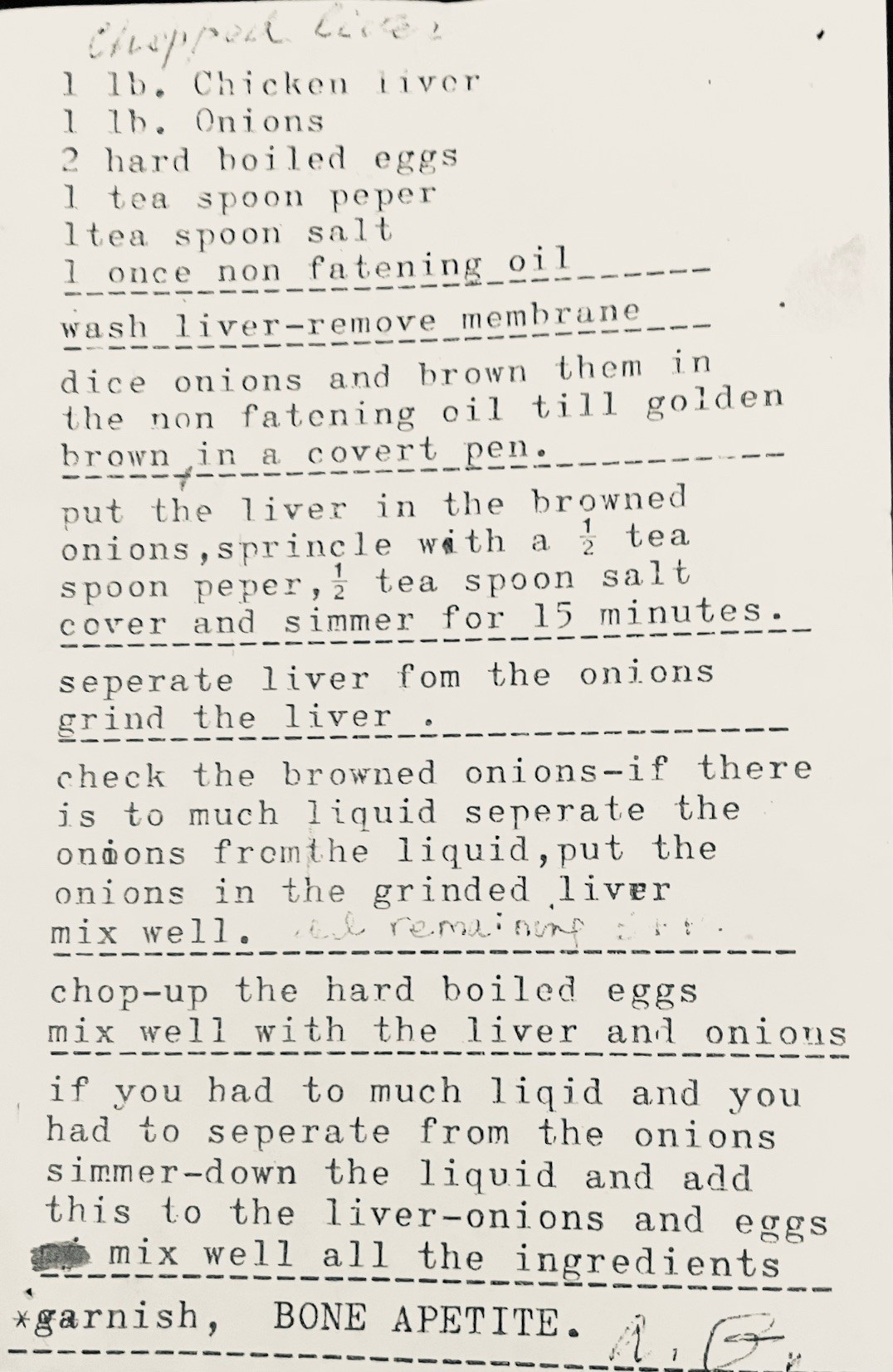

Aron Groer’s Famous Chopped Liver Recipe

Though schmaltz-less, this recipe for chopped liver has passed the taste test of countless purists. Annie Groer added a third hardboiled egg for texture. If you don’t use all of it for decorating, add what’s left to the liver. Serve with matzoh, bread, crackers or crudites. Or eat it directly from the bowl with a spoon.

4 to 6 servings

Ingredients:

1 pound chicken livers

2 tablespoons peanut or canola oil

1 pound yellow or sweet onions, cut into about 1/2-inch dice

1 teaspoon salt

1 teaspoon freshly ground black pepper

3 large eggs, hard-cooked and peeled

Directions:

Wash the livers and remove and discard the membranes. Set aside.

In a skillet over medium heat, heat the oil. Add the onions, cover and cook, stirring occasionally, until soft and golden, 7 to 10 minutes.

Add the whole livers to the skillet and sprinkle with salt and pepper. Reduce the heat to medium-low, cover and simmer gently until cooked through but still juicy, about 15 minutes. Remove from the heat.

Using a slotted spoon, immediately transfer the livers to a food mill or meat grinder, leaving the onions and their juices in the skillet, and grind the livers while still warm. (You may pulse the livers in a food processor, but be careful to leave some chunks. You don't want a smooth pate.) Transfer the mixture to a bowl.

Using the slotted spoon, add the onions to the ground liver, leaving the juices in the skillet. Stir gently to combine. If the mixture appears to be too dry, add some of the liquid in the skillet, a little at a time, until the desired consistency is attained. Season with salt and pepper to taste.

Coarsely chop 2 of the hard-cooked eggs, add them to the liver mixture and stir

gently to combine. Check again if the mixture is too dry and, if necessary, add more liquid from the skillet.

Take the remaining egg and separate the white from the yolk. Using a sharp knife, thinly slice the white into strips and place on top of the chopped liver. Using a small-holed grater, grate the yolk over the entire surface of the chopped liver. Cover and refrigerate for 2 hours.

My Father's Chopped Liver

Back in the 1970s, shortly before I left on an extended hippie trek through Latin America, my widowed, worried Daddy implored me for perhaps the zillionth time to please, please be careful. Well, of course, I always replied with a hint of exasperation. But because Aron Groer was a world-class alarmist and I, his only daughter, was part brat and part adventuress given to taking up with fascinating strangers, I humored him by suggesting we choose a secret phrase in case I was abducted by anti-imperialist guerrillas.

This cockamamie scheme required that before he paid out the first peso in ransom, he would have to hear me personally utter the words "gehakte leber," Yiddish for chopped liver, to signal I was still alive. It made perfect, if far-fetched sense, since chopped liver was one of the two signature dishes -- the other being gefilte fish -- he had developed after my mother's untimely death when my big brother Steve and I were barely in our teens.

In its way, Aron's chopped liver was a kind of mortar that held our little family together. It may have looked like a post-monsoon mix of mud and gravel, but it tasted like heaven and drew us to the kitchen table like some Proustian madeleine.

Mounded atop a Hunnakah latke, slathered on matzoh during Passover, spread daintily on celery sticks during the occasional diet, sandwiched between pillowy slices of challah most other times, or simply snarfed down by the spoonful directly from the container when no one was looking, Aron’s chopped liver became more than just a splendid example of the culinary arts. It became an edible expression of a grieving father’s love, prompting me to joke that in our working-class household, his vaunted chopped liver recipe was a major part of my dowry.

Friends and family worldwide requested it for celebrations major and minor, or for no reason other than its fabulousness. I can't count the times Steve and I brought home school chums eager for a chopped liver fix. Lord knows how many batches I hand-carried back to grad school in Wisconsin, and even to loved ones in New York City, arguably America's deli capital.

In his modest Maryland kitchen, Aron regularly achieved a near-perfect balance of sauteed chicken livers and onions, hard-boiled eggs, salt and pepper. Whether an added virtue or a grievous deficiency, however, this dish contained not a single yellow globule of schmaltz, known to most people as chicken fat, and to cardiologists as prime heart attack food.

Aron's livers were instead lubricated with cholesterol-free canola or peanut oil, which he endearingly identified as "non-fatening" in the recipe he typed for me ages ago. That linguistic lapse, plus several other phonetic misspellings, were understandable given that English was his fourth tongue, after Yiddish, Polish and French.

To purists, of course, schmaltz-less chopped liver is about as appealing as a tofu burger or carob mousse. Nonetheless, shortly before his 99th birthday, I wrote a Washington Post homage to his heart-healthy gehakte leber.

I have no recollection of him actually making chopped liver, or anything else for that matter, until my mother's untimely death in 1958. But in the early 1960s, he had an emotional reunion in Paris with his brother Moishe, and his sister Bronka, whom he had not seen since my parents bolted Warsaw for Paris in the early 1930s. By 1937, two years before Hitler marched into Poland and murdered most of their families, my father and mother arrived in Washington, DC, where she had relatives eager to help them achieve American citizenship. For this, I remain eternally grateful.

Here’s what you’re friends and family receive when you gift a subscription:

In-depth articles exploring the intersection of food and politics and featuring writers such as veteran journalist

Annie Groer.

Access to The American Table chatroom, where you can share YOUR OWN stories about the power of food.

Detailed and exclusive recipes

Bonus podcast episodes

Exclusive Documentary and Film Projects:

Access to all of our original media, including award-winning documentaries, an upcoming animated short film, “Somerville” and our ongoing web series, “Behind The Line,” where I cook with chefs from around the country and uncover their stories.